Yesterday the hull of the dive boat slammed into Steve’s head in heavy surf; this morning he looked like a cross between a teenager with chronic acne and a cooked lobster thanks to the mosquitoes and sun ravaging his skin. Yet bizarrely he was smiling. Not because of that lot – obviously. It was because today was his 38th birthday and he’d just climbed back into the boat after seeing his very first whaleshark. Soon after he saw and swam with his second and a third, but that was the reason he’d chosen to visit Mozambique.

The Eastern face of the Barra Peninsular near the town of Inhambane in Mozambique is a hotspot for the planet’s largest fish. They come to feed in the plankton rich waters and a dive industry has grown up around this annual migration. Not that diving is the best way to see whalesharks – far from it. They may look lumbering, but a 10 metre long shark on idle can still easily outpace a human in scuba gear. The best way to view whalesharks in their environment, therefore, is to snorkel.

I have seen whalesharks in several parts of the world – western Australia, the Maldives, Tanzania, Djibouti and Thailand, but until I went to Mozambique I’d always had to search for them. In Mozambique we simply came across them either on the way to a dive or coming back. One day we’d seen so many the dive master’s voice was getting a bit lacklustre when another shark was spotted.

Our enthusiasm had yet to be extinguished though and as the boat slowed near each shark eager splashes indicated another snorkeller had entered the water. There were only six people on the boat, so the shark didn’t feel crowded and none dived or showed any sign of irritation. Whalesharks in my experience are inquisitive creatures and quite often stop or turn towards snorkellers. If they are not in the mood to play, they simply carry on at a pace and leave humans flailing in the water. Or at worst, they sink slowly downwards aware that humans cannot follow.

As we neared one shark, the cox slowed to a crawl and lined the boat up parallel with the shark’s path of travel. I slipped into the warm Indian Ocean and made for the shark. The water was a graduated blue – the seabed out of view. The only things visible where a few small fish flitting in the surface chop. I put my head about the surface to check where the boatman was pointing and I was still heading in the right direction.

The water in the distance grew darker as the shark emerged out of the visibility edge. She swam directly at me seemingly unfazed by my presence. Her sensory system would have told her I was there long before she could see me, but a predator my size would need to think very hard or be very hungry to take on an 8 metre long shark so she wasn’t perturbed and carried on. As she neared, I could see the lack of anal claspers meaning she was female and surprisingly she had very few hangers on. Whalesharks, like other ocean wanderers pick up all manner of hitchhikers such as remoras and pilotfish. This one was fairly free.

I stopped and waited. At first she started to veer off and my heart sank a little as I thought she was going to pass me by at a distance. Instead though, she turned. Soon my vision was filled with spotted whaleshark and still she kept coming, dipping below just before we collided. I lay as flat against the surface as I could, but had I wanted to, could have reached down and touched her head. I was also conscious that following her head was a large dorsal fin and then a tail, both of which stuck up a long way. She knew that too and her dorsal drifted by just a few centimetres from my mask and most importantly – groin (A tonne worth of fish slamming into my nether regions would be the complete opposite of pleasant!). It was a thrill to have interacted with such a huge animal, but then it always is fun when whalesharks are around as I discovered.

I travelled to Mafia Island, off Dar Es Salaam, not to see whalesharks, but to discover the outcome of a marine park that I helped create. I found out, while there, that whalesharks are often seen on the other side of the island. So we took a trip out with a fisherman to see what we could find. We used other fishing boats to pinpoint the sharks, because they target the large animals too. They don’t catch them, but have formed a sort of loose symbiotic relationship. The fishermen surround the feeding sharks with a large net to catch the fish that swarm around the sharks. The sharks are released to continue feeding while the fishermen haul in a net full.

It’s a system that works well and the sharks don’t seem disturbed by this behaviour.

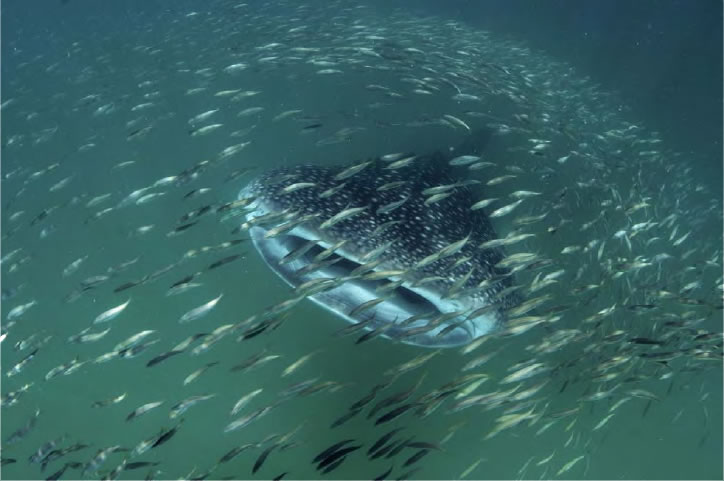

As we approached one shark – a small female of around six metres – she turned towards the boat and went to go beneath us, only she didn’t come out the other side. I dipped my head in and saw her vertical in the water beneath us, using the boat’s shadow as we were using sunglasses to protect us from the glare. The water was misty and the white sandy seafloor reflected the harsh sun causing bad glare beneath the surface. The only thing I could imagine the shark doing was resting her eyes. Several of us slipped in to join her and she moved around, but stayed below in the boat in its shadow surrounded by a shoal of small fish – the kind the fishermen caught.

One photograph I captured had the shoal of fish swimming between me and the shark. It won highly-commended in the Shell Wildlife Photographer of the Year competition in the highly fought over Underwater World category.

One photograph I captured had the shoal of fish swimming between me and the shark. It won highly-commended in the Shell Wildlife Photographer of the Year competition in the highly fought over Underwater World category.

The gather that never was And its underwater photography that took me to Djibouti. I went to photograph the annual gathering of whalesharks in the Gulf of Tadjoura. Here, whalesharks gather for a few weeks at the end of the year to feast in the plankton rich water. I went to record this spectacle… and failed. A week before, the boat crew were seeing upward of ten sharks in one place. We saw about ten sharks in one week. Not a bad haul admittedly, but not what I was expecting, but that is wildlife for you. One minute it’s frolicking in numbers difficult to comprehend the next it’s buggered off somewhere else.

As the largest fish in the sea and one of the largest creatures on earth, you’ expect whalesharks to be easy to find. But little is known of their movements across the planet and only a few gathering spots have been found. Some like Ningaloo reef in Western Australia, Gladden Spit in Belize and Richelieu Rock in Thailand have been well documented. Others such as the East African coast areas of Mozambique, Tanzania and Djibouti are what could be referred to as up and coming, but how the sharks migrate between them and where they go and feed between times remains a mystery. Some research is being done, but compared to many land animals; it is in its infancy. Which means that anyone who encounters a whaleshark may have something to offer biologists studying them? So the next time you are out on a boat in the tropics look out for a dark smudge just below the surface, it could just be a whaleshark, and if you have the time I wholeheartedly recommend getting in the water to experience it.